Overview

The outlook for the global economy has deteriorated causing an increase in financial market volatility this year. More uncertain global growth prospects and declines in inflation expectations could produce sustained economic and financial weakness as well as intensified concerns about global financial stability. The IMF pointed out in its latest Global Financial Stability Report in April 2016 that the world economy will grow 3.4% this year, up from 3.1% in 2015. But, there are four significant downside risks to the prediction: China; the impact of falling commodity prices on producers; the fragile state of some emerging market economies such as Russia and Brazil; and the possible disruption that could be caused by the US Federal Reserve raising interest rates when other central banks, including the European Central Bank (ECB) and the Bank of Japan, are still providing additional stimulus.

Protracted geopolitical risks are indicated by the increasing frequency and intensity of tensions. The conflict between Russia and the Ukraine is still unsolved, and the crisis in the Middle East is deepening. In addition, it is increasingly difficult for Europe to cope with the growing number of migrants. Moreover, before Brexit, the EU was seen as a centre of stability in the international system. Europe is in the process of switching from a source of stability to a source of international instability. The Greek crisis, the migrant crisis, the rise of populism and Britain’s vote to quit the European Union is causing turmoil not only in Europe, but also to the rest of the world. Most economies are still recovering from the financial crisis, and spill overs from the vote could be destabilizing in both short and long term. All these tensions have an unfavourable impact on the economic growth of EU member states, hinder investment and structural reforms, and through the deteriorating market sentiment they pose a financial stability risk that is becoming common.

The international environment and financial markets

Fears of a second serious financial crisis within a decade have been heightened by the turbulence in markets since the start of 2016. A connected sequence of financial disturbances hit the global economy and the financial system over the past decade, which lead to a weak and fragile financial system and took us back to call for the healthy environment before crisis. This is reflected in the calls for Normalization. There are four main factors that have been driving risk perceptions this year;

Worries about global growth and the inflation outlook

Increased political uncertainty related to geopolitical conflicts, political discord, terrorism, refugee flows, or global epidemics loom over some countries and regions, and if left unchecked, could have significant spill overs on financial markets. More uncertain global growth prospects and declines in inflation expectations have increased downside risks to the baseline growth forecast, as noted in the April 2016 World Economic Outlook (WEO). In the absence of additional measures that deliver a more balanced and potent policy mix, episodes of market turmoil may occur, tightening financial conditions and eroding confidence. Further shocks and a broader loss of confidence could impart more damage to the global economic baseline and increase the risks of sliding into an adverse downside scenario of persistent disinflationary pressures and rising debt burdens.

While underlying drivers of US growth are broadly improving, downside risks remain. Market participants have become worried that higher interest rates, and tighter financial conditions more generally, could materially weigh on growth. Moreover, excess capacity and high unemployment have seen aggregate euro area inflation steadily decline, and there is a real risk that the currency union could face persistent deflation. Other major advanced economies are facing similar difficulties, partly as a result of sustained weakness in oil prices. Deflation increases the burden of debt by increasing real interest rates, which can hamper economic growth. Moreover, deflation may pose difficulties for central banks in stimulating economic growth, particularly if accompanied by reduced inflation expectations. Furthermore, emerging market economies have undergone several severe shocks in recent quarters and its growth continues to slow across most economies.

The unfavourable market assessment of inflation and policy interest rate expectations could produce sustained economic and financial weakness in various countries. If the growth and inflation outlooks degrade further, the risk of a loss of confidence would rise. In such circumstances, recurrent bouts of financial volatility could interact with balance sheet vulnerabilities. Risk premiums could rise and financial conditions could tighten, thereby creating a pernicious feedback loop of weak growth, low inflation, and rising debt burdens. Low nominal growth and weakening fiscal positions would increase government debt burdens, with the ratio of debt to GDP rising 4 to 22.9 percentage points above the baseline across advanced economies by 2021, and 3.9 to 15 percentage points across emerging market economies. These negative disruptions to global asset markets, operating through financial channels, could materially worsen economic and financial stability.

Uncertainty about China

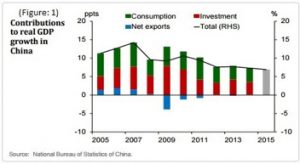

China is now such a big force in the global economy that it inevitably affects the rest of the world. It is the second largest economy and the second largest importer of both goods and commercial services. Given the emergence of China as a key contributor to global growth in recent decades, it is not surprising that the analysis of spill overs from a slowdown in China’s GDP growth has attracted considerable attention over the last few years, with the analytical coverage of its implications for the global economy intensifying during the second half of 2015, noted the IMF. According to National Bureau of Statistics in China, the real GDP growth was 6.9% in 2015, down from an average of 8.5% over 2010-14 and 10% over the previous decade as shown below in (figure: 1). Currently, the economic growth in China continues to slow, as the economy moves towards a consumption-led growth model.

A sharp reduction in investment growth has been the primary driver of the slowdown, and this is expected to continue as the economy matures. While investment will be replaced to a large extent by services and consumption growth, economic growth is expected to be lower compared to China’s previous growth model. After all, China’s growth rate remains high relative to everywhere else, but there is increased uncertainty about the economy and potential policy missteps, as China tackles domestic and external imbalances. The shift away from an export and investment-led growth model is also reducing demand for commodities used in physical investment, such as iron ore, contributing to the pressures facing commodity producing countries. China is such a large buyer of industrial commodities that the possibility of lower than expected sales to the country has also undermined the prices of copper and aluminium, for example. China consumes about 50% of some raw materials, and so far, its economic slowdown has therefore had the most acute impact on commodity-related sectors. East Asian economies: Malaysia, Thailand and South Korea, which depend on trade with China’s manufacturing sector, are suffering a dramatic slowdown as the Chinese economy focuses on tackling corruption and boosting consumer demand.

In fact, China confronts a number of critical policy challenges as it transitions to a growth model driven increasingly by consumption and services, rather than public investment and exports. This transition may become bumpy at times, but a strong commitment to reform and effective policy implementation with clear communication are essential. China’s financial and corporate sector vulnerabilities have been rising. These vulnerabilities will need to be addressed promptly as the economy moves toward a more market-based financial system, including the exchange rate. In this context, the internationalization of the renminbi and greater financial integration with global markets represent an important step forward not only for China, but for the international monetary system. To stem the outflow of capital and depreciation of the renminbi, liberalisation of the capital account has slowed and authorities have enforced existing capital controls more rigorously. While this has helped to slow the depletion of China’s foreign exchange reserves, market participants remain concerned about the potential for a sharp currency depreciation, which could generate further financial market volatility.

Falling commodity and oil prices

Financial markets have experienced periods of heightened volatility recently as uncertainty surrounding the global economic outlook has increased, particularly between December 2015 and February 2016. Sustained low commodity prices are placing increased pressure on commodity producing countries, especially in emerging markets. Authorities in some commodity producing countries have taken action to support their economies. Russia has liquidated half of its sovereign wealth fund to fill the budget gap left by low oil prices, and several other countries adopted similar measures.

The IMF downgraded the outlook for many emerging countries, notably Russia, Brazil and South Africa. For commodity producers – the likes of mining firms that extract iron ore and steel manufacturers – a global slowdown threatens their profitability. Many have seen their share prices plunge as analysts judge them to be overvalued and where commodity producers lead, other businesses often follow. The list of developing nations suffering the after effects of the slowing global economy and the slump in oil prices grows every week. Last year, Brazil slid into a recession made worse by a corruption scandal toppled the government. Venezuela is expected to default on its loans after oil revenues dry up. Nigeria, Russia and the Middle Eastern producers are also badly hit by falling oil prices, leaving government budgets under risk.

Ultra-low commodity prices could cause big problems for more than just the banks and investors who lend to mining firms. For instance, the copper price has more than halved since 2011. This is largely because China’s slowdown means the metal, used in electrical wiring among other things, is not in such demand. The economy of some countries – such as Zambia, for instance – are built almost entirely on copper. Low metals prices could force mining-dependent countries to default on their debts, spreading the problem to sovereign debt markets too.

Since June 2014, oil prices have fallen by 60% and commodity prices have fallen by almost 40% and because companies in emerging markets had been building large debt throughout the period of high commodity prices. Both companies and banks’ balance sheets are saddled with up to $3.5 trillion in over borrowing. The fall in oil and commodity prices in emerging markets results in both winners and losers, depending on whether countries are net commodity exporters or importers. As a result, the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) region is facing serious growth challenges in the face of weak oil prices, but serious efforts to reform spending and attempts to augment government revenues are expected to safeguard the region from a potential recession. According to a Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales (ICAEW), oil prices are expected to remain low until at least 2017, due to the continuation of current policy of the Organisation of Petrol Exporting Countries (OPEC) and increasing concerns over growth in China and other emerging markets. The sustained low oil prices will erode existing buffers, like subsidies, more rapidly, threaten to undermine long-standing currency pegs, and slow economic growth further as trade, investment and capital flows fall back.

Governments in some Middle Eastern oil producing countries have offered guarantees on debt to support the banking system. Support has also been increased for farmers in the European Union as the dairy prices remain low with global dairy supply continuing to increase. Many farmers now face a third season of negative cash flow. Some commodity producers have attempted to maintain revenues by holding output steady, which has contributed to over-supply in a range of markets. Nevertheless, some producers have come under pressure as their costs of production exceed current prices. This is particularly apparent in the US oil sector, where a number of producers have shut down and prospective investment has been pared back significantly.

Concerns about banks increasing debts in advanced countries

The US Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) announced its Normalization Policy which should ultimately return the Fed’s balance sheet and interest rates to September 2014 levels. In December 2015, the Federal Reserve System signalled four further interest rate rises to occur throughout 2016. However, recent weaker near-term indicators have slowed the pace of expected tightening. While underlying drivers of US growth are broadly improving, downside risks remain because market participants have become worried about raising interest rates. Moreover, concern regarding the health of US corporates increased in late 2015 and the first quarter of 2016, particularly relating to firms in the energy and mining industries struggling under low commodity prices. This contributed to the sharp increase in corporate credit spreads over the same period, although spreads have moderated somewhat in recent months (figure 3.12). Elevated credit spreads and low commodity prices could make it difficult for exposed firms to service debt, thereby reducing growth.

Indeed, the US have seen massive credit expansion, debts have ballooned in part because of the boom in shale oil and gas extraction in the US. Companies borrowed heavily to fund investment in shale when the oil price was high. US oil companies had $1.6tn of syndicated loans in 2014. Now after prices have tumbled, those debts look increasingly unsustainable. The firms that have high costs to extract oil are seeing their profits wiped out. The sheer volume of commodity-related debt poses challenges because it means that credit losses from commodity investments will be substantial for many investors. For example, $2tn of bonds had been issued by mining companies since 2010, many of them now rated as undervalue, meaning there is a high risk investors will not get their money back. Mining companies have suffered badly because they spent big when metals prices were high and cannot sustain their operating costs now that prices are low.

With the US Federal Reserve expected to raise interest rates in the coming months, the IMF warns that emerging market governments should ready themselves for an increase in corporate failures, as firms struggle to meet sharply higher borrowing costs. That could create distress among the local banks which bought much of this new debt, causing them in turn to rein in lending in a “vicious cycle” reminiscent of the credit crisis of 2008-09. Decreased loan supply would then lower aggregate demand and collateral values, further reducing access to finance and thereby economic activity, and in turn, increasing losses to the financial sector.

Cyclical pressures have hurt the outlook for bank earnings generation. Low inflation and low growth act to reduce loan demand and therefore the outlook for future bank earnings. In the US, expectations of a steepening yield curve weakened along with delayed prospects of monetary policy normalization. In the euro area, rising risks of low inflation and low growth pushed bank valuations down, and weak sentiment was reinforced by poor earnings results from some banks. A further cyclical challenge to bank profitability comes as more central banks push rates into negative territory.

As European banks own a significant amount of sovereign debt, concerns about indebtedness of some European sovereigns may be reinforcing banking system difficulties. Geopolitical risks in Europe, including discord related to large refugee inflows and recent terrorist attacks, are increasing the potential for political instability. Also, the British exit resulted in elevated financial market volatility due to uncertain implications for EU and global economic growth. Stock markets around the world suffered massive losses and currencies tumbled, due to the uncertainty caused by the UK vote to leave the EU. Indeed, the uncertainty over future trade arrangements has already reduced confidence in sterling and investment could well be discouraged. As a result the UK’s vote to leave will almost certainly have serious consequences on everything from financial markets to European policy decisions to political careers to the stability of the bloc. This will be felt quickly on the international level and impact the global financial stability.

European bank profitability has declined significantly since the global financial crises, in part due to the sluggish economic recovery and slow bank balance sheet repair. Falling interest rates have also contributed, by narrowing lending margins and reducing the return on banks’ holdings of government bonds. Negative interest rates are proving particularly challenging, as banks have been reluctant to pass them on to depositors due to concerns about a significant outflow of deposits, which are a primary source of bank funding. However, with subdued economic activity limiting available lending opportunities, negative rates may incentivise banks to loosen lending standards, which could increase financial vulnerabilities.

Concluding Remarks

The increasingly globalized nature of the financial system creates a need for international cooperation in the area of financial supervision and regulation. Policy-makers need to build on the current economic recovery and deliver a stronger path for growth and financial stability by tackling a triad of global challenges – legacy challenges in advanced economies, elevated vulnerabilities in emerging markets and greater systemic market liquidity risks. Progress along this path will enable the world’s economies to make a decisive break toward a strong and healthy financial system and a sustained recovery. As the IMF noted, policy-makers need to deliver additional measures to create a more balanced and potent mix of policies to reduce risks and support growth. If not, market turmoil could recur and intensify, and create a pernicious feedback loop of fragile confidence, weaker growth, tighter financial conditions, and rising debt burdens. This could tip the global economy into economic and financial stagnation. In such a scenario, the world output could be almost 4 % lower than the baseline over the next five years and this would be roughly equivalent to forgoing one year of global growth.

In a world where economic recovery remains uneven across advanced economies, monetary policies are expected to remain different. While the US is likely to proceed with a gradual normalization of policy, although at a slower pace than previously envisaged, the euro area and Japan are expected to continue, or even deepen, their monetary accommodation, including through negative interest rates. This creates movements in foreign exchange markets, with the appreciation of the US dollar, which warrants careful monitoring and strong macroeconomic and prudential policy frameworks initially in the banking sector to contain risks in potentially affected countries.

The major advanced economies are no longer the only source of financial spillovers, the financial spillovers from emerging economies – to both advanced and to other emerging economies – have become stronger since the global financial crisis. As the emerging markets have contributed more than half of global growth over the past 15 years. Crises in emerging market economies have often had financial repercussions in other countries. The Latin American debt crisis of the 1980s, Mexico’s economic crisis of 1994–95, and the East Asian and Russian financial crises of the late 1990s are prominent examples of high macro-financial volatility in emerging market economies that spilled over significantly to other emerging market economies and to advanced economies. In this context, the financial regulatory reform agenda should be completed and implemented. As part of this, the resilience of market liquidity should be reinforced by putting in place adequate policies and oversight of asset management and financial market structures. This is crucial to safeguarding global financial stability and supporting global growth.

Finally, the global financial crisis demonstrated the downside of interconnectedness while revealing a range of systemic vulnerabilities. Currently, the world is facing a truly daunting set of challenges; the instability anywhere can be a threat to stability everywhere. As the global financial system continues to recover and adapt to significant transformative change, major collaborative efforts are required to enhance the global financial system. They should focus on how to build a more efficient, resilient and equitable international system. The global financial system must reinforce its contribution to sustained economic growth and enhance the global financial stability.

Comments