The Islamic State has lost almost all of its territory across Iraq and Syria. However, since 2014, it has underhandedly entered the Khorasan region, which covers territory in parts of Iran, Pakistan and Afghanistan. Officially established on 10 January 2015, the affiliate group is known as Islamic State-Khorasan Province (IS-K)—often referred to as Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant-Khorasan (ISIL-K). Upon entry into the province, IS-K became the target of the Afghan Taliban as a competing jihadist group.

IS-K’s growth is attributed to defections from minor groups across Afghanistan and Pakistan pledging their loyalty to IS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. Numbers increased from not only fighters fleeing Iraq and Syria, but also defectors from the Afghan Taliban. Members of other militant groups also shifted their allegiance, such as from Pakistan’s Tehreek-e-Khilafat—which was aligned with al Qaeda—and Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP). Other al Qaeda affiliates, like the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) also sided with IS-K. Defections occurred as individuals believed in stricter principals of the Islamic State as a whole than that of their own respective groups. While the Afghan Taliban, for instance, seeks to rid the U.S. and other forces from Afghanistan and maintain control in the country, the Islamic State wants to rule the Muslim world in its entirety across borders. This ideology was more appealing and bolstered by the groups bravado seen across propaganda media outlets.

As such, current estimates believe there is anywhere between 1,000 to 2,000 Islamic State fighters in Afghanistan. IS-K is continuing its campaigns to further its expansion into the northeastern part of the country, where it is currently active in the Jawzjan and Sar-e-Pol provinces and Kandahar.[1] While IS-K fighter numbers are minor in comparison to the numbers once present across Iraq and Syria, the group has proven to be a formidable force in the Khorasan province by maintaining an active force in ungoverned spaces. This article briefly addresses the groups background and provides a brief overview of their activities in the region. What can be deduced is that IS-K is continuing to muddy the waters in a war-torn Afghanistan and rivaling an Afghan Taliban group, which further complicates policy needed to stabilize the country.

Leadership and Allegiances

Extending into the Khorasan Province was not easily achieved, and it continues to be just as difficult. Abdul Rauf Khadim was a short-lived leader of IS-K, being killed in a U.S. drone strike shortly after the groups establishment. Hafiz Saeed Khan was officially the first emir, or leader, of IS-K. He was a former commander in the Pakistan Tehrik-e Taliban (TTP), but pledged allegiance to al-Baghdadi in 2014. Kahn was killed in July 2016 by a U.S. drone strike in the Achin district of Nangarhar and replaced by a former Afghan Taliban commander, Abdul Haseeb Logari. He was killed in a firefight by U.S. and Afghan special forces in the Nangarhar province in April 2017. It is believed that Haseeb Logari led the 8 March 2017 attack on the Sardar Mohammad Daud Khan Hospital in Kabul. According to U.S. Forces in Afghanistan (USFOR-A), IS-K fighters dressed as hospital workers to initiate the attack, which ultimately killed over 100 people. Abdul Rahman Ghaleb replaced Haseeb Logari, but followed the fate of his predecessor with a short-lived leadership role, having been leader for only three months between April 2017 and July 2017. Qari Hekmat was the leader until his death in April 2018. Based in northern Afghanistan in the Jawzjan Province, he extended IS-K operations across northern Afghanistan into Faryab and Sar-e-Pol Provinces. The groups current presumed commander, Mawlawi Habib Rahman, is believed to be in custody by the Afghan government.

The variety of leadership shows IS-K’s reach. The group has an extraordinary ability to forge alliances with local militant groups that have generally not been very welcoming. In Pakistan, for instance, IS-K forged alliances with Lashkar-e-Jhangvi al-Alami, Jundallah, factions of TTP, Lashkar-e Islam (LeI), and Lashkar-e-Khorasan.[2] Members from both the Afghan Taliban and Pakistan Taliban defected and joined IS-K. As previously mentioned, the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) also pledged its allegiance to the IS-K branch.[3] The IMU is noteworthy as it has historically been tied to the TTP, al Qaeda (AQ) and the Haqqani Network, which is allied with the Afghan Taliban. Beginning in 2014, a rift was noticed between the IMU and the Afghan Taliban, particularly with Taliban leadership. When the Taliban’s leader, Mullah Omar, was confirmed to have been killed, the IMU switched allegiances to IS-K in August 2015. However, this relationship was only temporary. An internal schism resulted in a new IMU faction that condemned the IS-K in June 2016 and reverted to its original loyalty to the Taliban and AQ.[4]

Despite the leadership changes, the group continued to recruit enough fighters to keep the Afghan Taliban at bay and stretch across the northern part of Afghanistan. It is also indicative of their marketability to lure high ranking individuals from competing jihadist groups to lead IS-K. The Islamic State as a brand is still relevant to some even though they are not at all popular in Afghanistan.

Activity

Islamic state propaganda and recruitment tactics were first noticed in 2014 in the Khorasan province. From Kabul to Jalalabad to Peshawar, Islamic State propaganda was calling on individuals to join their fight. They were particularly calling on individuals to defect from existing groups, such as the Taliban, which continues to be their greatest rival. Nangarhar province was one of the areas with the greatest number of battles between IS-K and the Afghan Taliban. In 2015, the Taliban was forced to retreat in several districts, which IS-K claimed. The group’s number of fighters continued to steadily increase. Overall, IS-K interfered with the Taliban’s efforts to attack Afghan and U.S. forces in the country. According to data compiled by START, there were approximately 241 incidents between 2014 and 2017 across 97 cities or districts in Afghanistan alone. The top five are shown in Table 1 below.

Table 1: Number of IS-K Attacks in Afghanistan, 2014-2017

| District/City | Number of Attacks |

| Jalalabad | 35 |

| Kabul | 27 |

| Achin district | 18 |

| Kot district | 15 |

| Darzab district | 10 |

Source: Perpetrators: Khorasan Chapter of the Islamic State, National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START). (2018). Global Terrorism Database [Islamic State-Khorasan Province]. Retrieved from http://www.start.umd.edu/gtd/search/Results.aspx?perpetrator=40371.

According to the data, 105 attacks over the three-year period occurred in these five areas (which is 44 percent of the total). There were a total of 96 attacks recorded in Pakistan, of which the highest are shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Number of IS-K Attacks in Pakistan, 2014-2017

| City | Number of Attacks |

| Quetta | 18 |

| Peshawar | 13 |

| Karachi | 9 |

| Islamabad | 3 |

| Rawalpindi | 3 |

| Gichk | 3 |

| Lahore | 3 |

| Parachinar | 3 |

Source: Perpetrators: Khorasan Chapter of the Islamic State, National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START). (2018). Global Terrorism Database [Islamic State-Khorasan Province]. Retrieved from http://www.start.umd.edu/gtd/search/Results.aspx?perpetrator=40371.

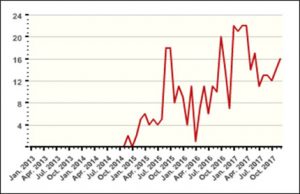

According to the data, 55 IS-K attacks occurred in these areas in Pakistan (which is 57 percent of the total). There were only 44 areas of IS-K attacks in Pakistan, which is significantly lower than Afghanistan. Overall, as shown in Figure 1 below, 2017 experienced the highest numbers of IS-K attacks.

Figure 1: IS-K Attacks, 2014-2017

Source: Line-chart downloaded from: “Perpetrators: Khorasan Chapter of the Islamic State,” National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START). (2018). Global Terrorism Database [Islamic State-Khorasan Province]. Retrieved from http://www.start.umd.edu/gtd/search/Results.aspx?perpetrator=40371.

As the line chart shows, the greatest number of IS-K attacks occurred between January 2017 and May 2017. This is likely due to successful campaigns by U.S. and Coalition forces that expelled Islamic State forces from Iraq and Syria in droves. The Khorasan province was the next suitable environment for IS remnants to occupy.

As a result, IS-K targeted specific areas to expand their operations and generate a formidable fighting force. The group had a leader, a deputy, and a council that consisted of intelligence, finance, propaganda, and education committees. [5] It is difficult to put an exact number on IS-K’s fighting force, but approximations can help provide an idea of how large the group has been and where it is now. Most of the controlled territory was in the southwestern province of Farah and eastern province of Nangarhar and parts of Helmand and other nearby provinces.[6]

Conclusion

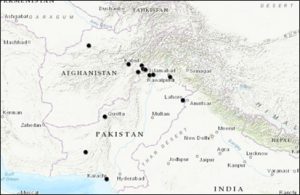

The porous border between Afghanistan and Pakistan makes is easy for fighters to easily cross over from one side to the other with the help of sympathizers and allies. As shown in Figure 2 below, attacks are clustered along the Afghanistan-Pakistan border (incidents are data from Table 1 and Table 2 above).

Figure 2: Afghanistan-Pakistan IS-K Attacks, 2014-2017

Source: Esri, HERE, Garmin, FAO, NOAA, USGS. Map created on www.arcgis.com. The data is not comprehensive, but sample data shown in Table 1 with 105 attacks and Table 2 with 55 attacks.

Despite the frequent change in leadership and massive loss in numbers, IS-K is resilient and a continued nuisance to the Afghan Taliban.

General John Nicholson reported in February 2017 that Afghan and coalition forces had reduced IS-K’s fighter numbers by nearly half and territory control by two-thirds.[7] In April 2017, the U.S. military used a ‘Massive Ordnance Air Blast’ (MOAB) against an IS-K tunnel and cave system in Nangarhar. As previously mentioned, current IS-K numbers range between 1,000 and 2,000 fighters. Most recent reports indicate that most of the fighters are in the southern Nangarhar province, with pockets of fighters in eastern Kunar province. Even though the Taliban has far greater numbers than IS-K, they are continuing to struggle to eradicate the group from the Khorasan province and other smaller pockets where they may exist. The intensity of the Islamic State in the Khorasan is no less than it was in Iraq and Syria. So far in 2018, the United Nations Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA) reported that over half of the civilian casualties in the country were caused by the IS-K.[8] The group continues to utilize suicide bombings, hit and run tactics, improvised explosive devices, among other attacks.

The U.S. Department of State designated the group as a Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO) on 14 January 2016. The group is continuing its efforts to claim territory in the Khorasan province and maintains a steady propaganda machine that recruits enough fighters to battle the Afghan Taliban as well as U.S. and coalition forces. As U.S. CENTCOM Commander General Joseph L. Votel recently stated, the Islamic State has been making use of “high-profile attacks in places like Jalalabad and in Kabul, trying to inflict as many causalities as they can, whether it’s on the Afghan security forces or whether it’s on Afghan civilians, and using the shock of this violence to increase their exposure.”[9] The debate over IS-K’s lethality and relevance is still ongoing, but what is certain is the concern over the threat they pose remains at a high level.

Endnotes

[1] Katzman, Kenneth and Clayton Thomas, “Afghanistan: Post-Taliban Governance, Security, and U.S. Policy,” Congressional Research Service (CRS), 13 December 2017, Page 20. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/RL30588.pdf.

[2] See also: Jadoon, Amira, Nikaissa Jahanbani and Charmaine Willis, “Challenging the ISK Brand in Afghanistan-Pakistan: Rivalries and Divided Loyalties,” CTC Sentinel, Volume 11, Issue 4, April 2018. https://ctc.usma.edu/challenging-isk-brand-afghanistan-pakistan-rivalries-divided-loyalties/.

[3] Roul, Animesh, “Islamic State Gains Ground in Afghanistan as its Caliphate Crumbles Elsewhere,” The Jamestown Foundation, Terrorism Monitor Volume 16, Issue 2, January 26, 2018. https://jamestown.org/program/islamic-state-gains-ground-afghanistan-caliphate-crumbles-elsewhere/.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Jones, Seth G., James Dobbins, Daniel Byman, Christopher S. Chivvis, Ben Connable, Jeffrey Martini, Eric Robinson, and Nathan Chandler, “Rolling Back the Islamic State,” RAND Corporation, 2017. Page 158-159, 161, and 175. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR1912.html.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Jadoon, Amira, Nakissa Jahanbani and Charmaine Willis, “Challenging the ISK Brand in Afghanistan-Pakistan: Rivalries and Divided Loyalties,” CTC Sentinel, Volume 11, Issue 4, April 2018. https://ctc.usma.edu/challenging-isk-brand-afghanistan-pakistan-rivalries-divided-loyalties/.

[8] See: “Civilian Deaths in Afghanistan Hit Record High,” UN News, 15 July 2018. https://news.un.org/en/story/2018/07/1014762.

[9] Media Availability with General Joseph L. Votel, Commander, U.S. Central Command, in the Pentagon. 8 August 2018. https://www.defense.gov/News/Transcripts/Transcript-View/Article/1597394/media-availability-with-general-joseph-l-votel-commander-us-central-command-in/.

Comments